Looking Back On The Future

2017

Flinn Gallery, Greenwich Library, CT, USA

Co-curators: Debra Fram, Barbara Richards and Dana Langlois

Featured artists: Anida Yoeu Ali, Chov Theanly, Chath Piersath, Heng Ravuth, Kong Vollak, Marine Ky, Lim Muy Theam, Mil Chankrim, Neak Sophal, Ouer Sokuntevy, and Yim Maline

Visit website for more https://flinngallery.com/cambodia-looking-back-future/

Scroll down for exhibition images and statement. Or skip to the statement now.

Exhibition Statement:

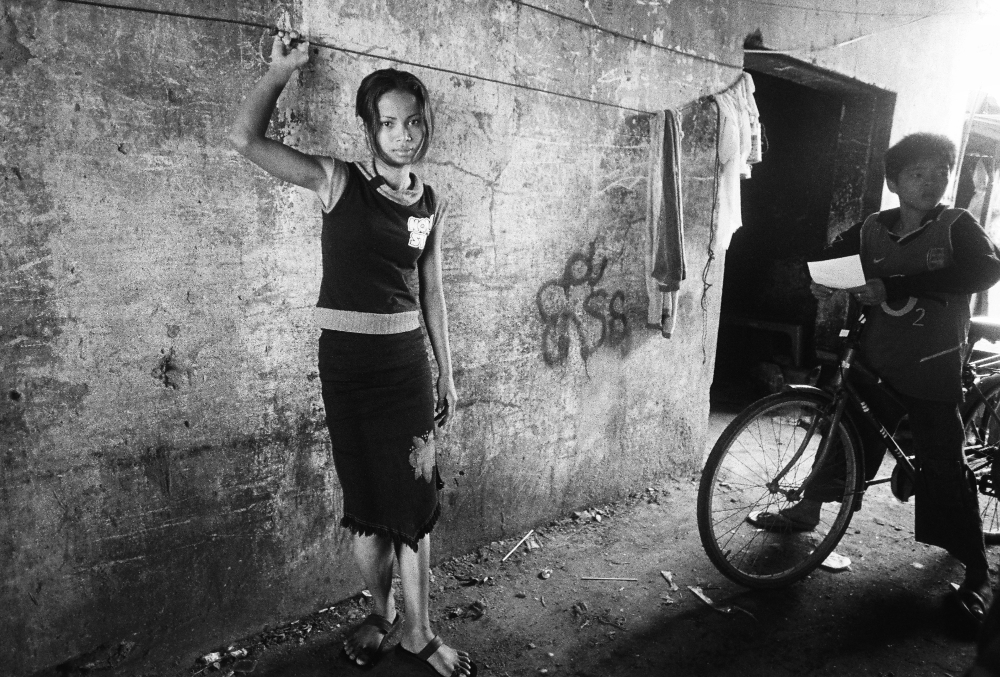

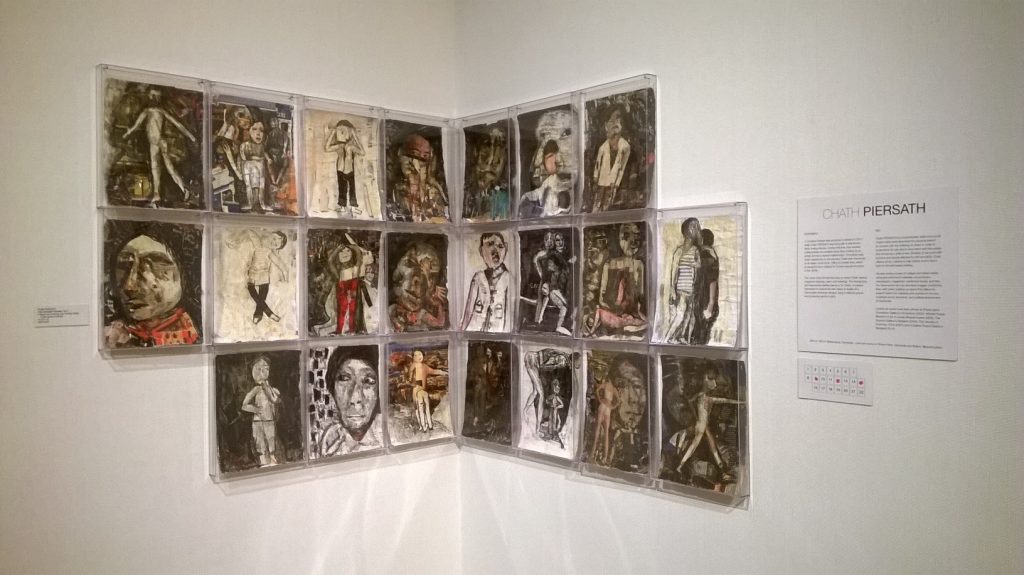

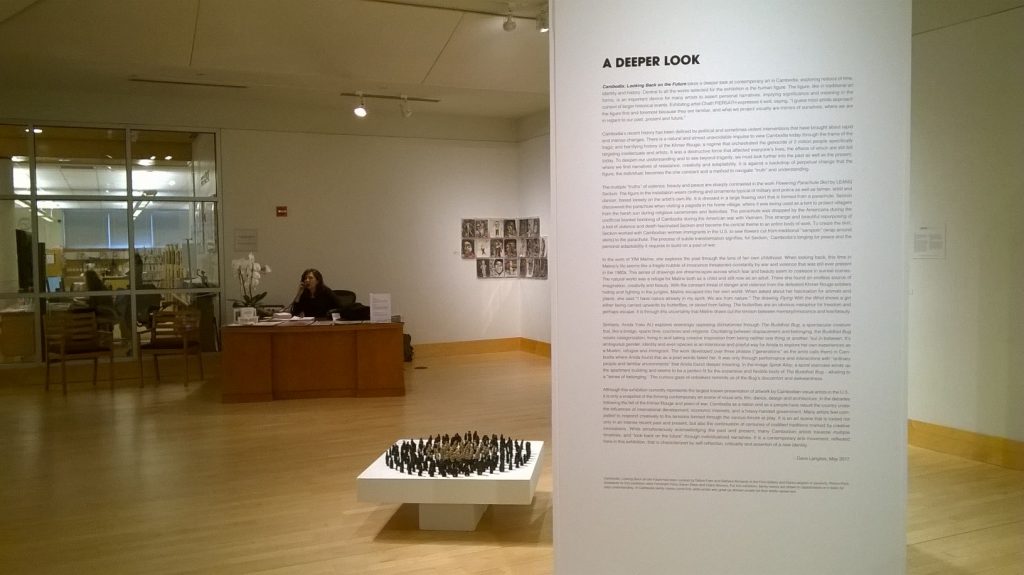

“Cambodia: Looking Back on the Future” takes a deeper look at contemporary art in Cambodia, exploring notions of time, identity and history. Central to all the works selected for the exhibition is the human figure. The figure, like in traditional art forms, is an important device for many artists to assert personal narratives, implying significance and meaning in the context of larger historical events. When talking about the figure, and his series The Constant Traveler, Chath PierSath says “I guess most artists approach the figurative first and foremost because they are familiar, and what we project visually are mirrors of ourselves, where we are in regard to our past, present and future.”

Cambodia’s recent history has been defined by political and sometimes violent interventions that have brought about rapid and intense changes. There is a natural and almost unavoidable impulse to view Cambodia today through the frame of the tragic and horrifying history of the Khmer Rouge, a regime that orchestrated the genocide of 2 million people specifically targeting intellectuals and artists. Without a doubt, it was a destructive force that affected everyone’s lives, the effects of which are still felt today. But to deepen our understanding and to see beyond tragedy, we must extend the frame in both directions of the timeline, where immediately before we will find the country’s independence from French colonial rule and the highly creative modernist period in the 1950s, to after the fall of the Khmer Rouge when current affairs are dominated by economic and foreign development agendas. It is against this backdrop of perpetual change that the figure, the individual, becomes the one constant and a method to navigate “truth” and understanding.

The multiple “truths” of violence, beauty and peace are sharply contrasted in the work Flowering Parachute Skirt by LEANG Seckon. The figure in the installation wears both military and dance ornaments and is dressed in a large flowing skirt that is formed from a discarded parachute. Seckon discovered the parachute when visiting a pagoda in his home village, where it was being used as a tent to protect villagers from the harsh sun during religious ceremonies. The parachute is believed to be American, dropped during the unofficial blanket bombing of Cambodia during the US war with Vietnam. This strange and beautiful repurposing of a tool of violence and death fascinated Seckon and become the central theme to an entire body of work, including the Flowering Parachute Skirt. To create the skirt Seckon worked with Cambodian women immigrants in the US to sew flowers cut from traditional “sampots” (wrap around skirts, often with floral designs) to the parachute-skirt, while clearly retaining the original form and material of the parachute. The process of subtle transformation signifies Cambodia’s longing for peace and the personal adaptability it requires to build on a past of war.

In the work of YIM Maline, she explores the past through the lens of her own childhood. When looking back, this time in Maline’s life seems like a fragile bubble of innocence threatened constantly by war and violence that was still ever present in the 1980s. This series of drawings are dreamscapes across which fear and beauty seem to coalesce in surreal scenes. The natural world was a refuge for Maline both as a child and still now as an adult. There she found an endless source of imagination, creativity and beauty. She crafted dolls and other toys from almost anything she could find because her family could scarcely afford to buy enough food much less something to play with. With the constant threat of danger and violence from the defeated Khmer Rouge soldiers hiding and fighting in the jungles, Maline escaped into her own world. When asked about her fascination for animals and plants, she said “I have nature already in my spirit. We are from nature.” The drawing Flying With the Wind shows a girl either being carried upwards by butterflies, or saved from falling. The butterflies are an obvious metaphor for freedom and perhaps escape. It is through this uncertainty that Maline draws out the tension of between memory/innocence and fear/beauty.

Similarly, Anida Yoeu ALI explores seemingly opposing dichotomies through The Buddhist Bug, a spectacular creature that like a bridge, spans time, countries and religions. Oscillating between displacement and belonging, the Buddhist Bug resists labels and categorization, living in and taking creative inspiration from being neither one thing or another, but in-between. It’s ambiguous gender, identity and even species is an intentional and playful way for Anida to explore her own experiences as a Muslim, refugee and immigrant. The work developed over three phases (“generations” as the artist calls them) in Cambodia, where Anida found that as a poet words failed her. It was only through performance and interactions with “ordinary people and familiar environments” that Anida found deeper meaning. In the image Spiral Alley, a spiral staircase winds up the apartment building and seems to be a perfect fit for the expansive and flexible body of the Buddhist Bug – alluding to a “sense of belonging.” But the curious gaze of onlookers reminds us of the Bug’s discomfort and awkwardness.

Although this exhibition represents the largest known presentation of artworks by Cambodian visual artists in the USA to date, it is only a snapshot of the thriving contemporary art scene of visual arts, film, dance, design and architecture. In the decades following the fall of the Khmer Rouge and years of war, Cambodia as a nation and as a people have rebuilt the country under the influences of international development, economic interests, and a heavy-handed government. Many artists either feel compelled or find creative inspiration, in the tensions formed through the various forces at play. Additionally, it is an art scene that is rooted not only in an intense recent past and present, but also the continuation of centuries of codified traditions marked by creative innovations. Cambodia’s ancient past that left remnants of sophisticated temple cities, and established the nation’s spiritual, ritual and cultural identity, is a persistent undercurrent in society today. Many Cambodian artists, deferent towards their past glory, while recovering from recent violent destruction and imagining the future, cross boundaries of time, “looking back on the future,” through individualized narratives. These intersecting timelines have shaped a contemporary arts movement, which is reflected in this exhibition, that is defined by self-reflection, criticality and assertion of a new identity.

– Dana Langlois, 2017