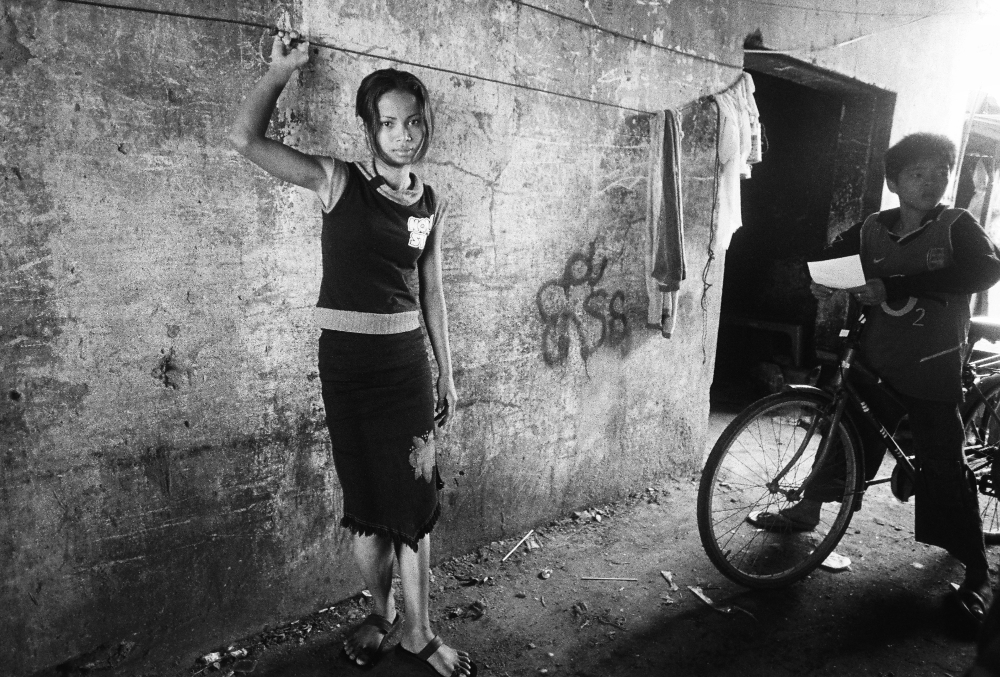

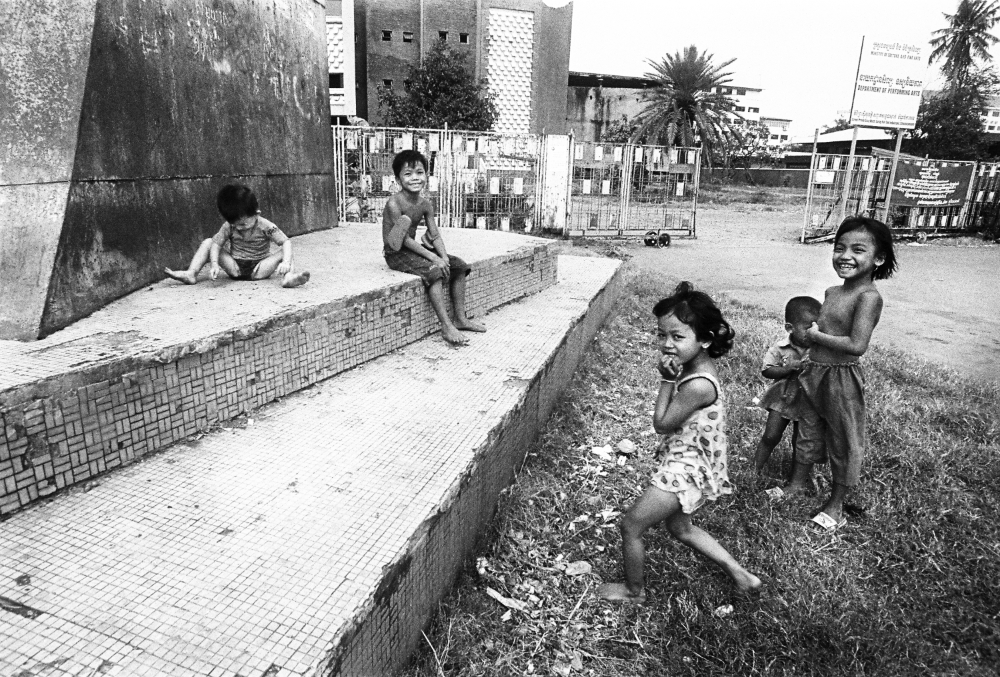

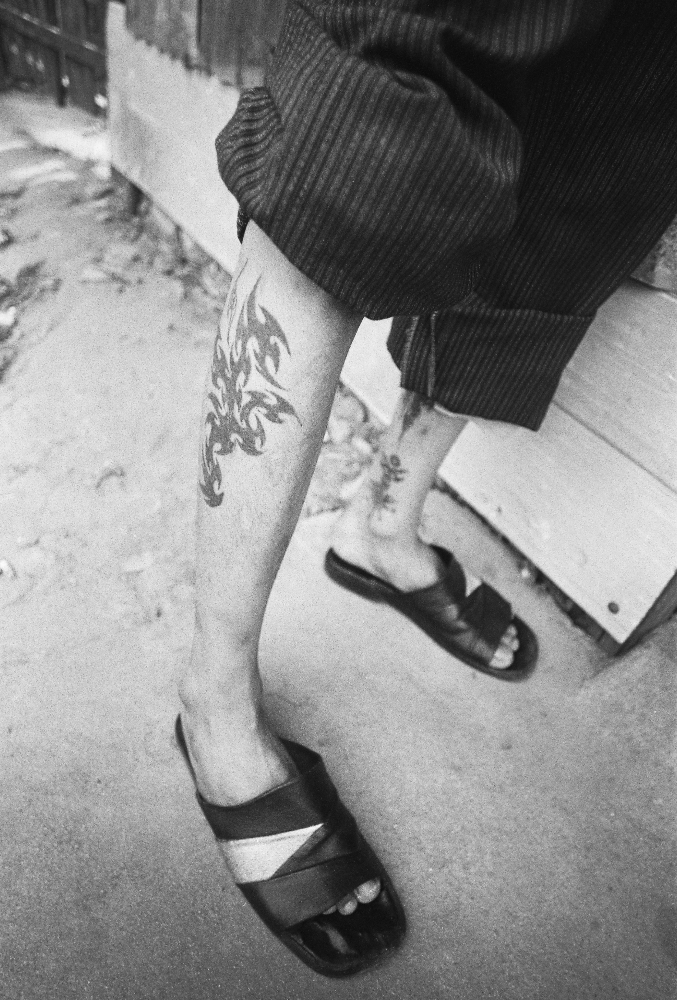

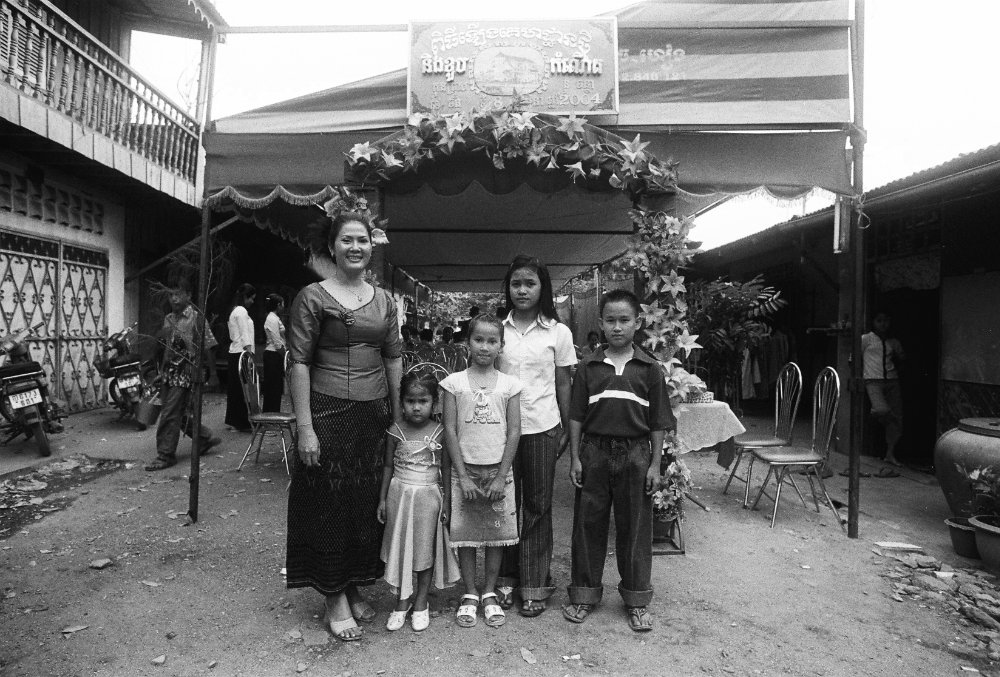

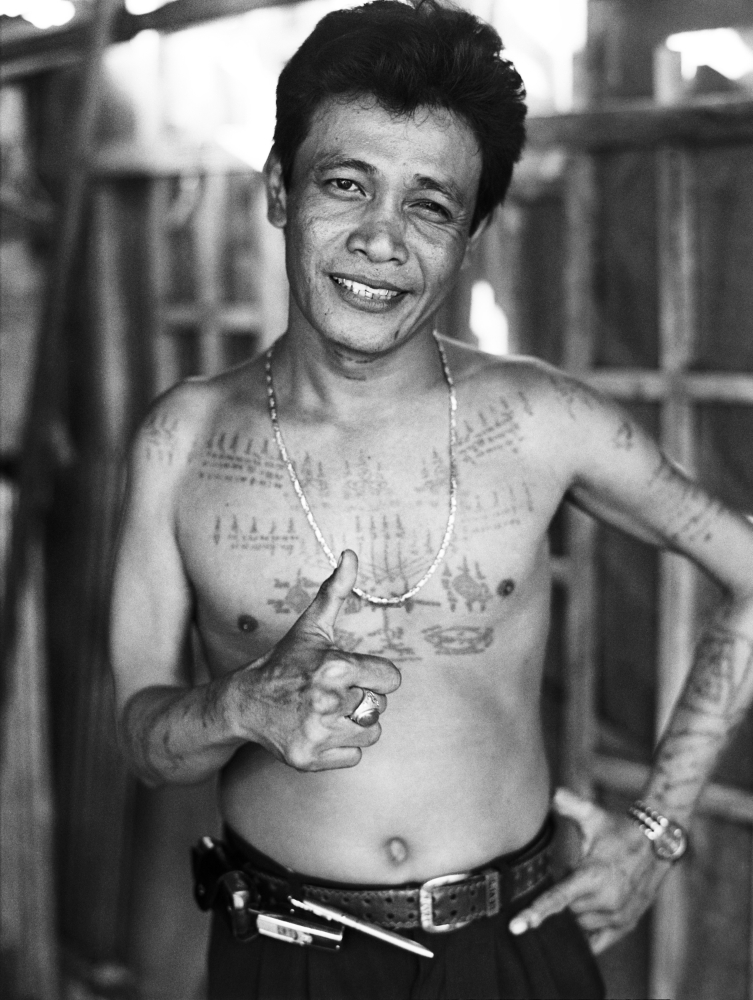

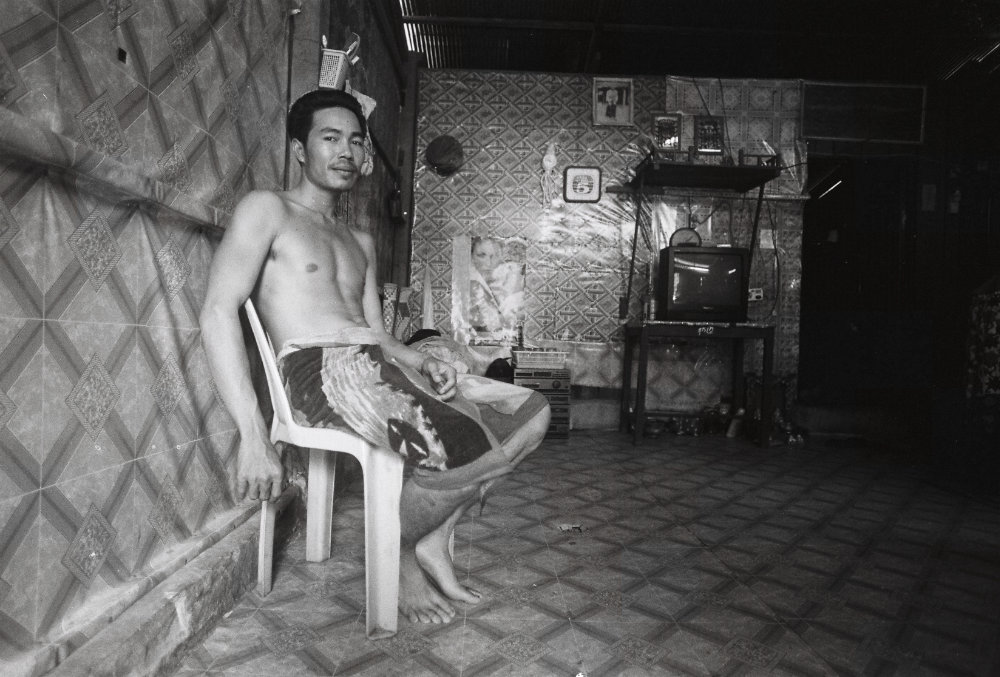

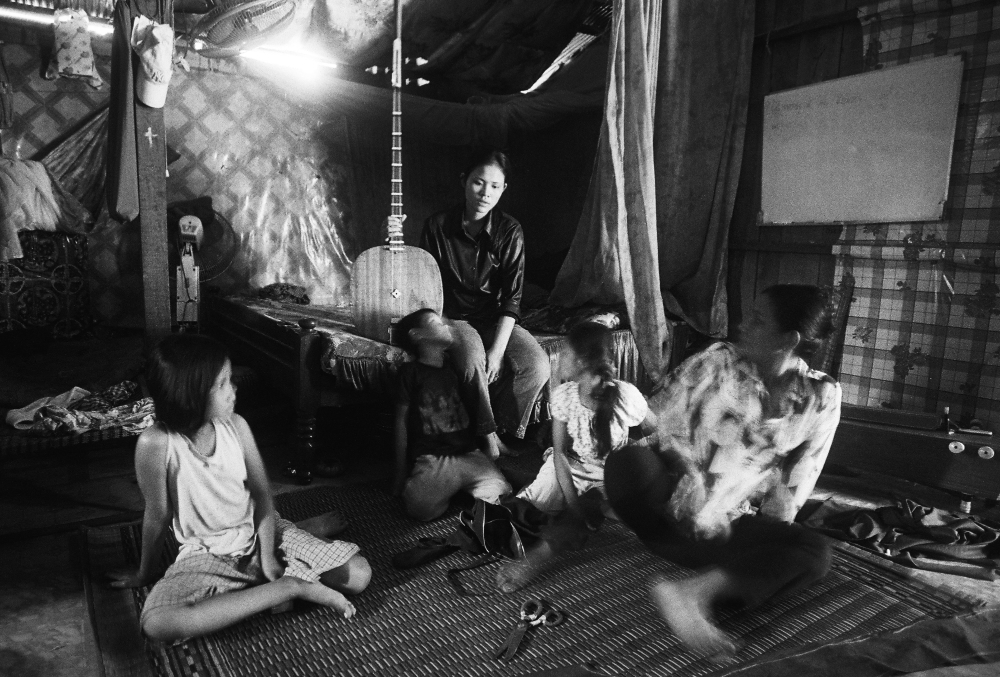

Dey Krahom (Red Earth) is a series of images and interviews that tell the story of a unique community of artists, performers and musicians before they were forcefully evicted from their homes to make way for a new development in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Over 800 families lived in homes built from scraps of metal and wood on marsh land that was filled in with the typical red earth of Cambodian soil, giving it its name. The village grew up around the National Theater and the White Building, architectural icons of the 1960s urbanism revival which have since been demolished. It was populated by people involved in bringing life to the theater, many of whom are considered masters of their art.

The National Theater had suffered significant damage in the 90s from a fire and since then many of the artists had little work. Their situation made worse by the country’s struggle to recover both economically and culturally from devastating war and Khmer Rouge genocide when 9 out of 10 artists were executed. In 2004, I spent months visiting the village and creating portraits of its residents. I was invited into people’s homes to see pictures of their performances and awards that they received. With pride, and great skill, they demonstrated their cultural talents. It was in that same year that the struggle for ownership of the land between the village and the authorities began. Over the next 6 years corruption and betrayal would eventually win and the villagers lost their homes with little or no compensation. Many were moved outside the city to even poorer living conditions and too far away from the city to earn a decent living.

Dey Krahom is a rare look into the lives of Cambodian artists whose work is essential to preserve cultural traditions and to pass it on to the next generation. It is the story of individuals who have survived genocide, and have faced challenges like poverty and land-grabbing with resilience and the power of their art.

Thank you to all who supported this project.

With special thanks to:

SAY Tola for research assistance and translation

Sebastien MAROT for translation

Sansitny RUTH for digital conversion

CHEY Chankethya and Prumsodun OK for help finding the artists

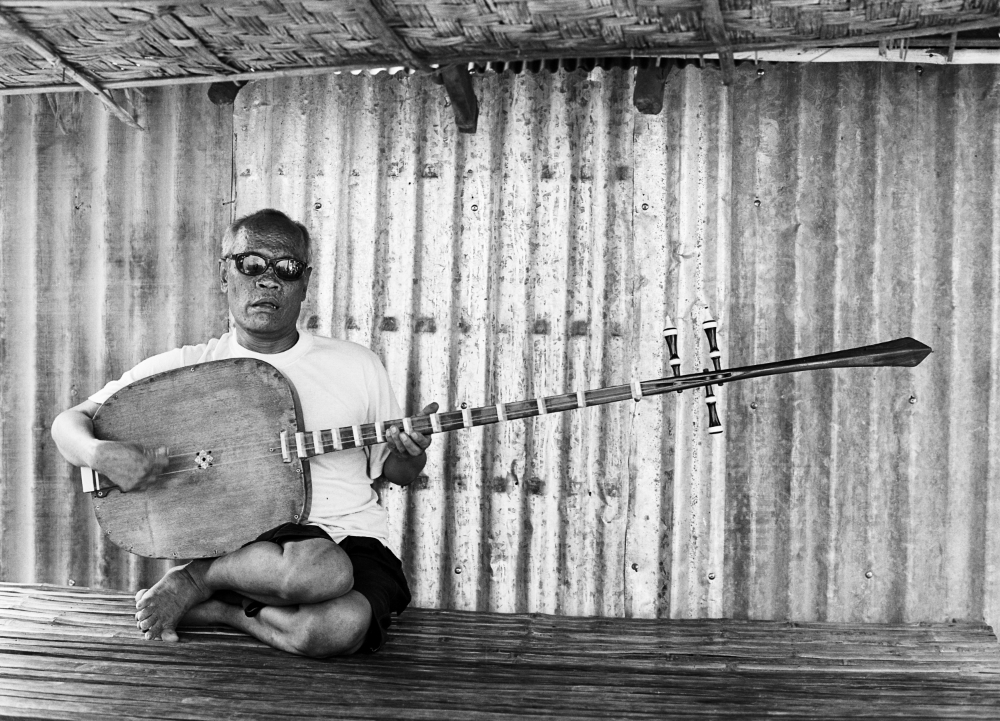

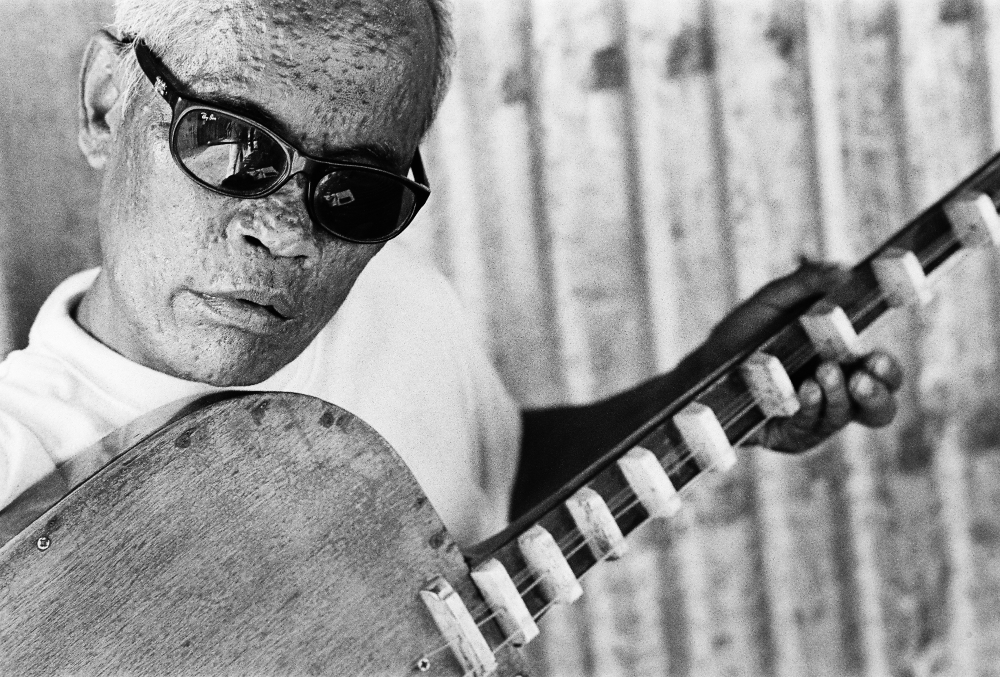

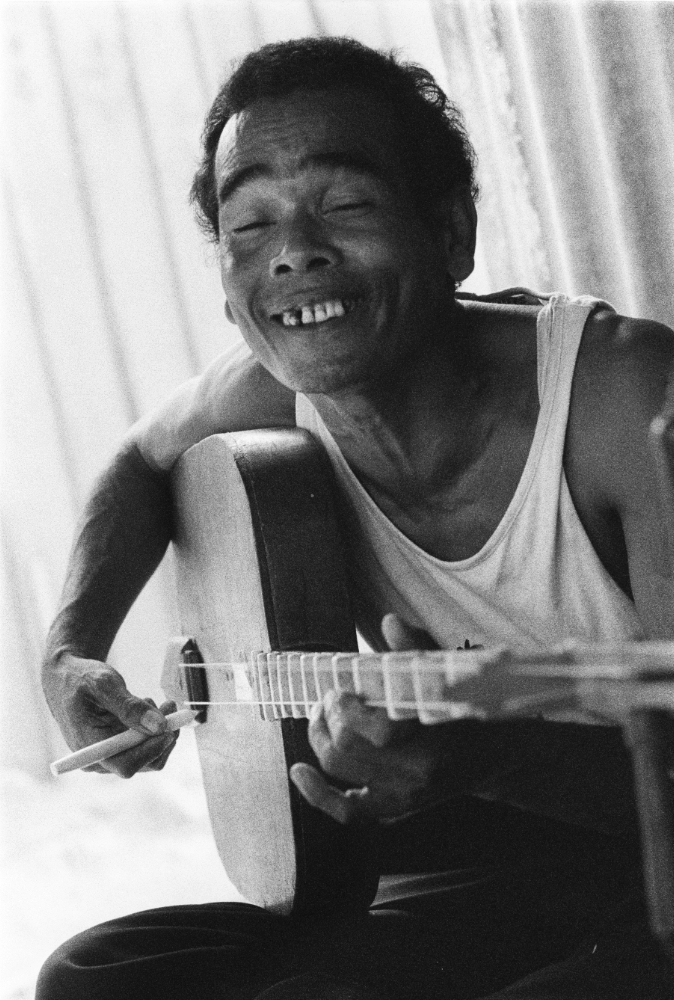

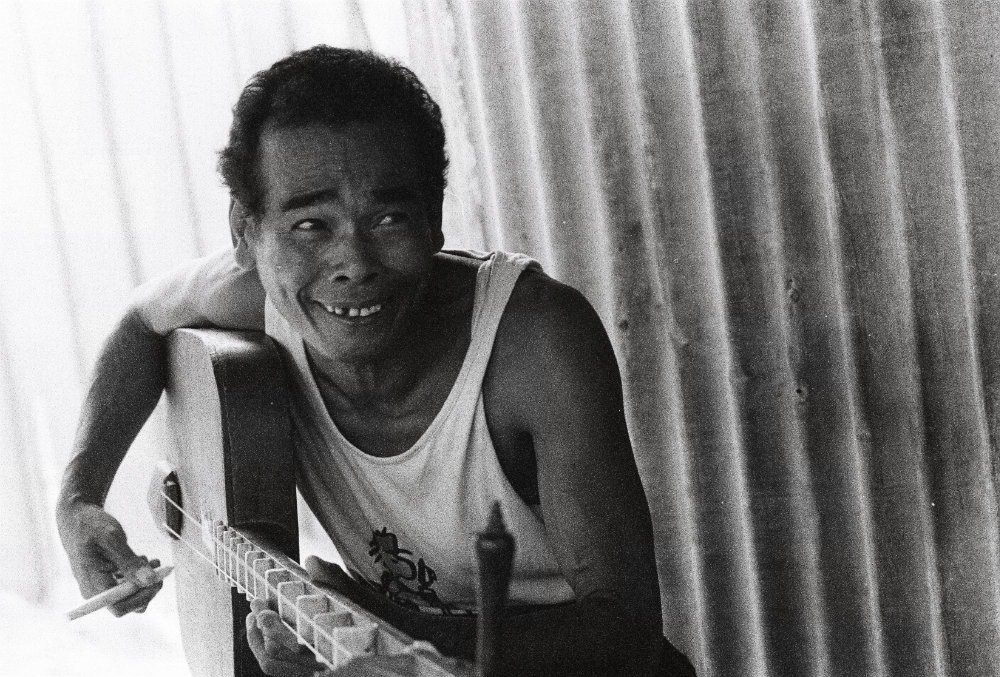

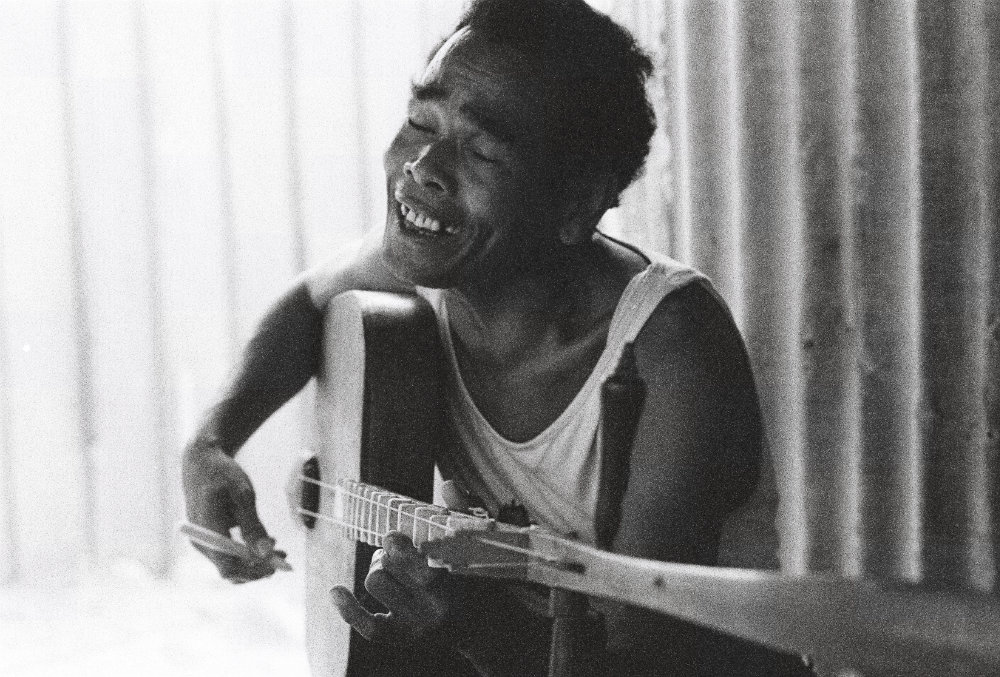

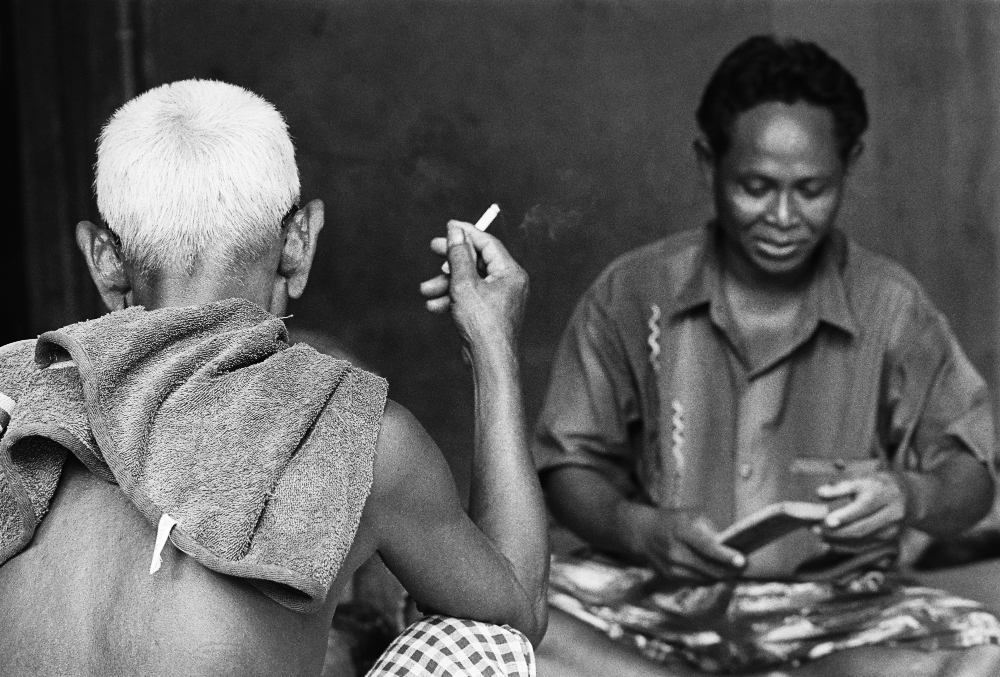

“I was actually interested to learn Chapei when I was around 10 or 11 because I thought that I’m just a blind person and I could not do anything other than use my voice.”

MASTER KONG NAI

Master Kong Nai, Chapei Dong Veng Musician

Born 1942 in Kampong Trach, Kampot

I first learned to sing and play Chapei when I was 13 years old and I went to study with my uncle Kong Tith. I was actually interested to learn Chapei when I was around 10 or 11 because I thought that I’m just a blind person and I could not do anything other than use my voice. Soon I was invited to sing for ceremonies. Sometimes I was invited to sing on the radio so that people could hear my message and my voice. I started to realize that Chapei could really provide me a way to make a living. I got married when I was 18 and my wife and I have ten children together.

With my family, I moved to the Dey Krahom area around 1991 or 1992. When I was living there, I taught some students including Ouch Savy, Pich Sarath, Sin Soy and my son Kong Boran. I stayed there until 2009 when the local authorities asked my family and other families to relocate. I asked them for compensation, but they said my request was unacceptable. Then I told them that if they cannot give me what I asked for, they could just give me a house to stay.

[Kong Boran, son of Kong Nai: A week after we left Dey Krahom, they used excavators to demolish everything. Since then, our community has been separated. I don’t know where some of them have gone to.]

I moved to the house they bought for us in 2009. As my age approached retirement, I decided to return to my hometown in 2015 because I wanted to be surrounded by my family.

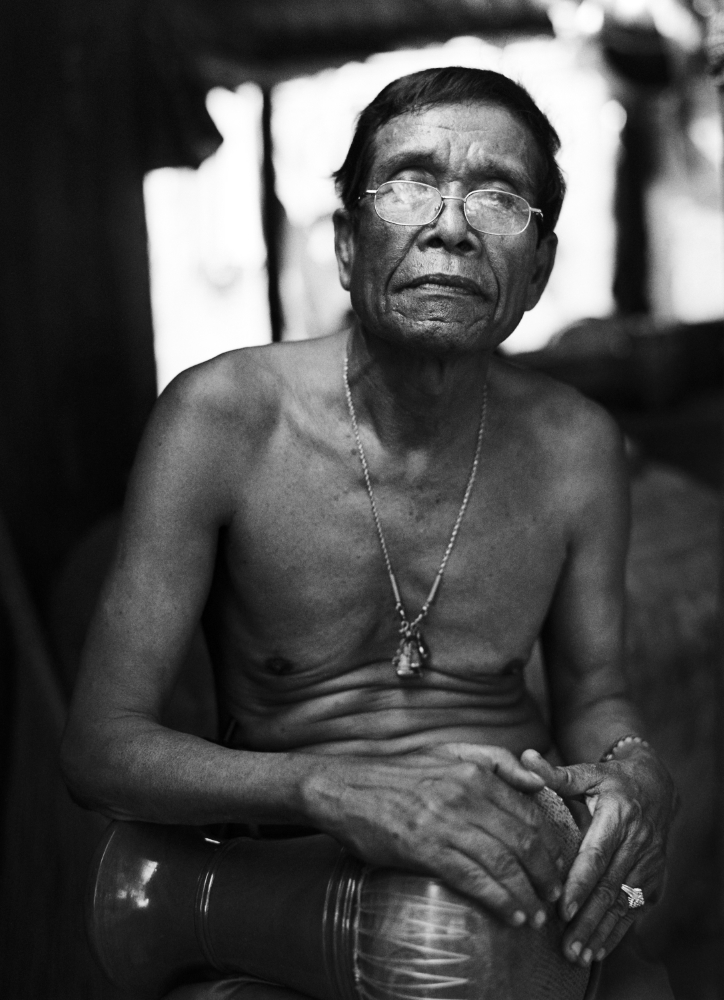

Master Soun San, Chapei Dong Veng Musician

1950 – 2017, born in Takeo

“Chapei is a priceless instrument to me because it supported me when we had nothing. I want to keep playing and spreading messages with it. I don’t want Khmer arts to be endangered.”

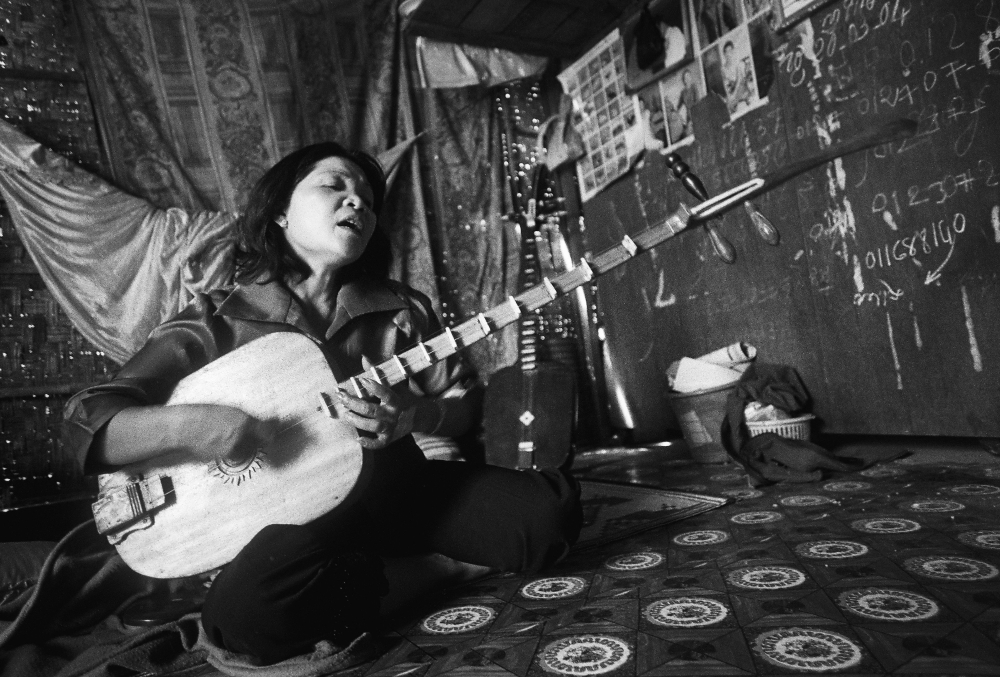

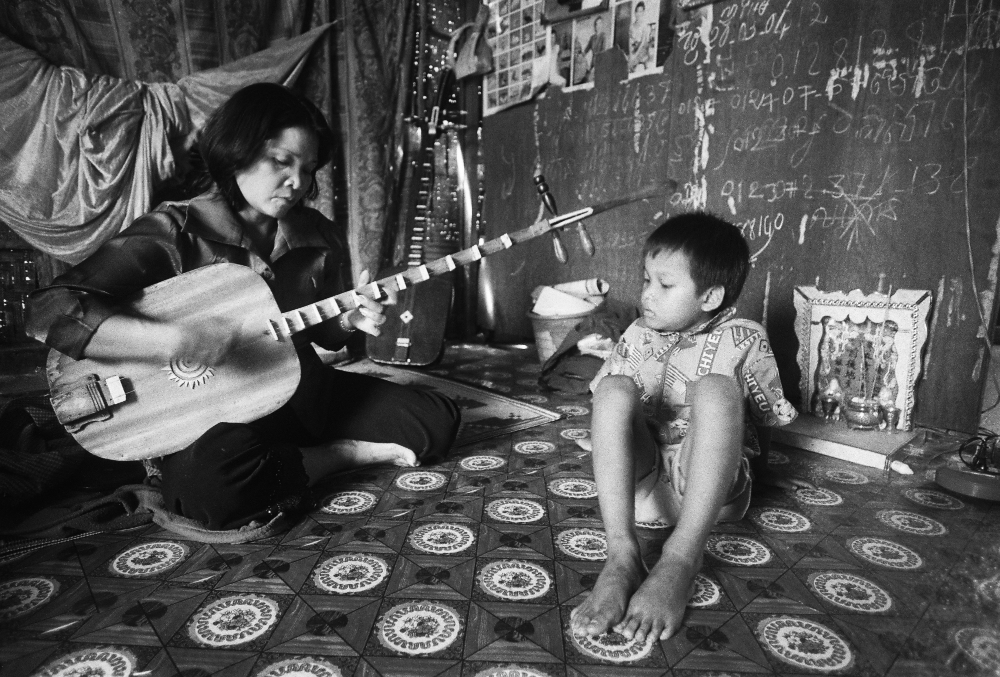

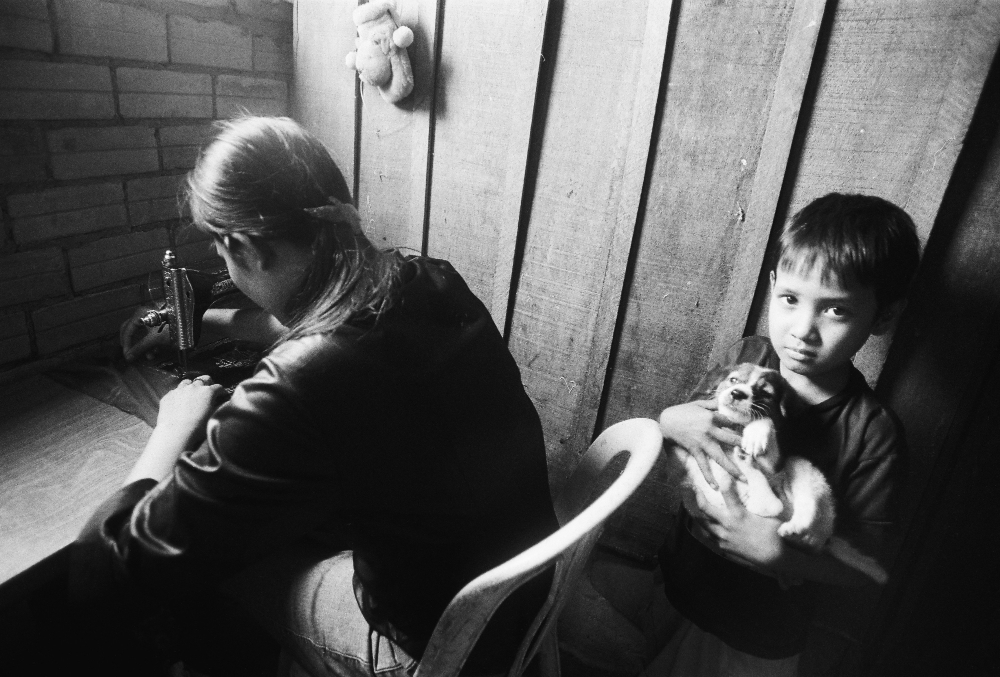

NEAKRU SIN SOY

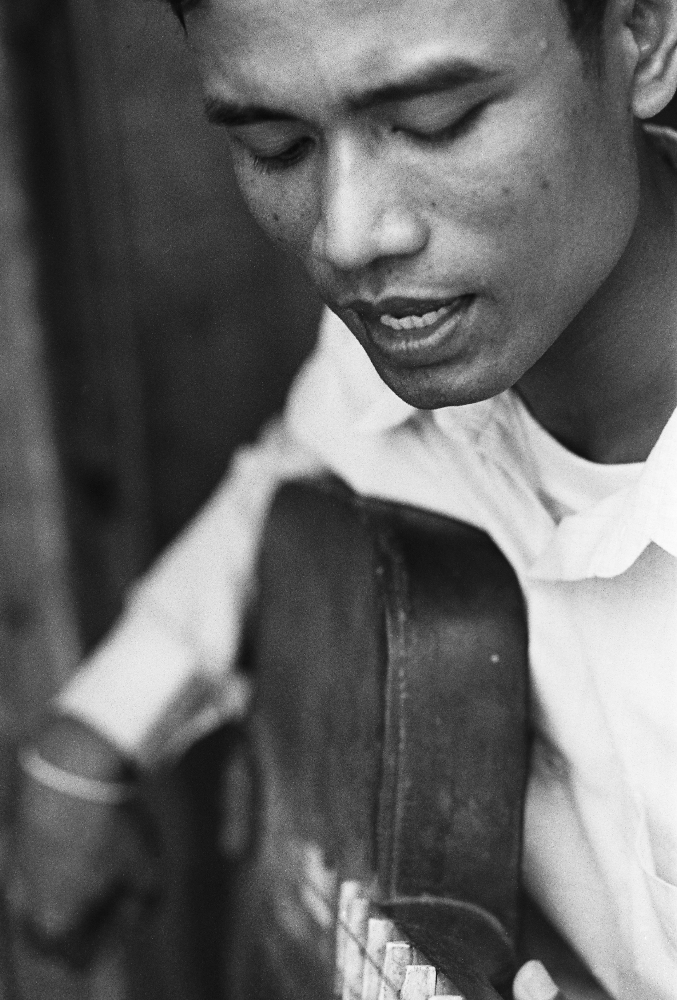

Neakru Sin Soy, Chapei Dong Veng Musician, Pleng Kar, Ayai and Lakhorn Singer

Born 1965 in Prek Kandeang Village, Prey Veng

I learned to sing Lakhorn when I was 11 years old, around the time of the Khmer Rouge regime. Since I could sing beautifully, a man came to tell me that Angkar is looking for singers and I would get rice to eat if I sang for Angkar. He was right. When I went to sing, they gave me rice, not just porridge like everyone else. They put me in “កុមារឈានមុខ” [Children Leap Forward]. I sang in a Lakhorn performance called “Dam Pheng.” The performances and songs were mostly criticizing the Lon Nol regime, while promoting the Angkar.

After the Khmer Rouge regime collapsed, I learned to sing Pleng Kar and Ayai. The government called me to work in the Department of Fine Arts and asked me to teach kids to sing. I sang for the government for many years and I travelled to many remote parts of Cambodia. Sometimes I would breastfeed my kids at the back of the stage. Life was miserable, but I could at least earn 15 to 20 dollars from a performance.

I moved to Dey Krahom in 1992. While living there, I received a lot of invitations to sing at many different events and ceremonies, and our life was a little better. I started to learn Chapei because I wanted to do something to support myself. My husband was also a Chapei player, but he spent all the money he earned with other girls and gambling. He only gave me 10,000 Riel (2.50$) per day to buy food to feed my children. I felt so frustrated. I went to ask Lok Krou Nai [Master Kong Nai] to teach me Chapei because I thought it could help me earn an income to support myself. Back then, not many women could play and sing Chapei. The Department of Fine Arts wanted to employ me for Chapei, but my husband said I could not work as I needed to take care of the children.

When we were told to leave Dey Krahom in 2009, they gave my family some money as compensation. We used that money to buy a house near Samroang Andet pagoda, which was on the outskirts of the city back then. I was a bit angry when they asked us to leave, but then I thought that the land did not really belong to me. What else could do but follow their decision.

After leaving, my husband kept spending money on girls. So we divorced five years later.

I have five children, three daughters and two sons. My daughters work in the factories and my sons are Passapp drivers. My life is very difficult now, yet I don’t want to reveal it because I don’t want the younger generation to think that they’ll be poor if they work in the arts.

Chapei is a priceless instrument to me because it supported me when we had nothing. I want to keep playing and spreading messages with it. I don’t want Khmer arts to be endangered.

Lokru Gnab Sat, Musician

“Those instruments were everything I had from my hard work over many years. At the end, nothing was left for me.”

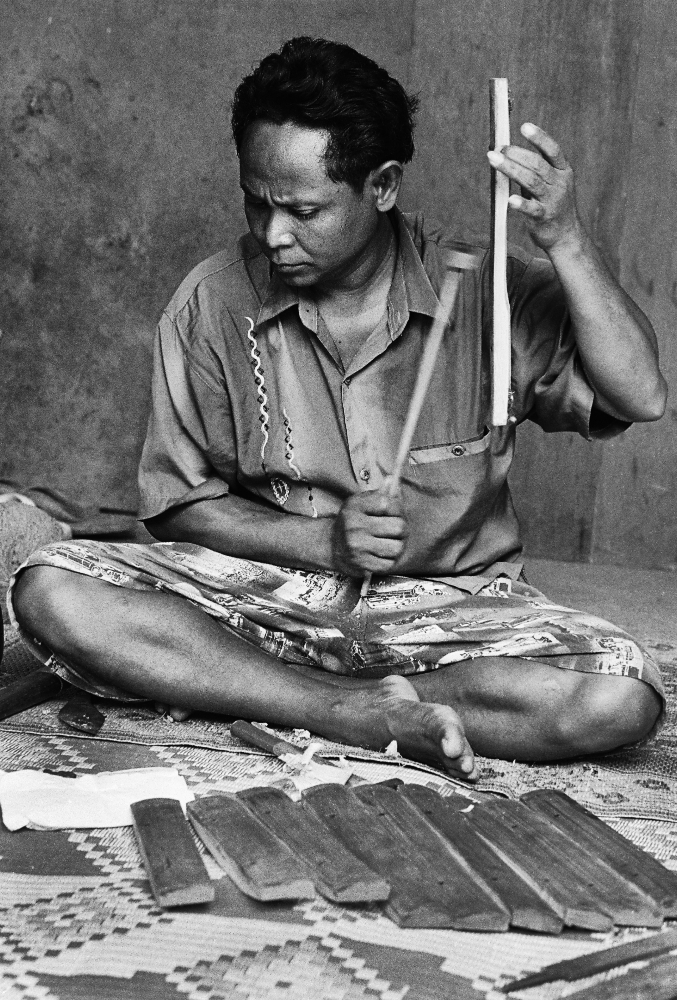

LOKRU MEAS MARY

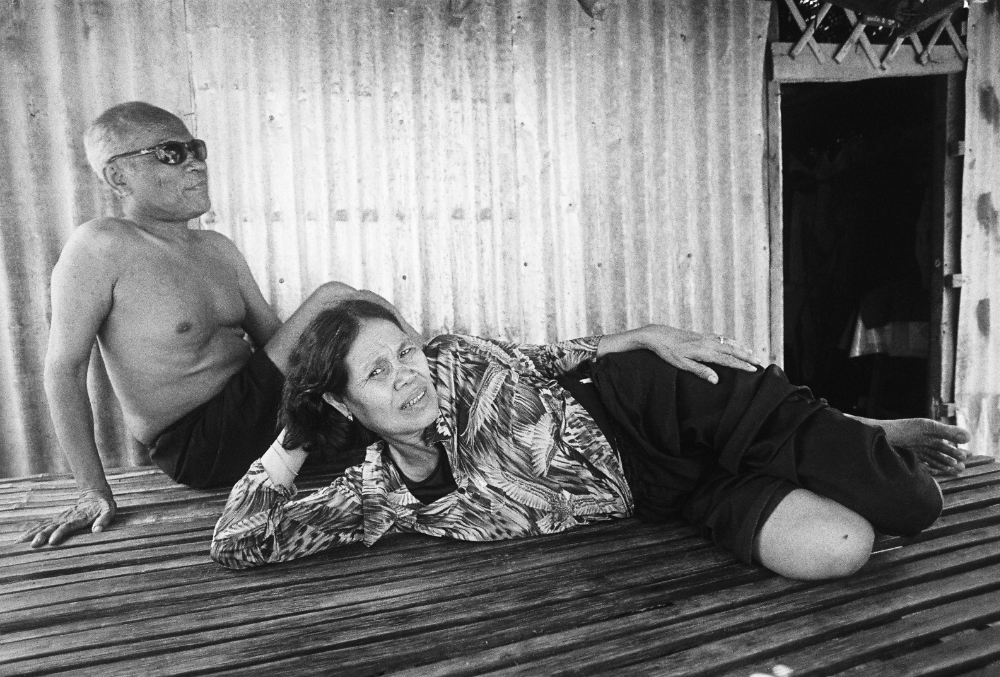

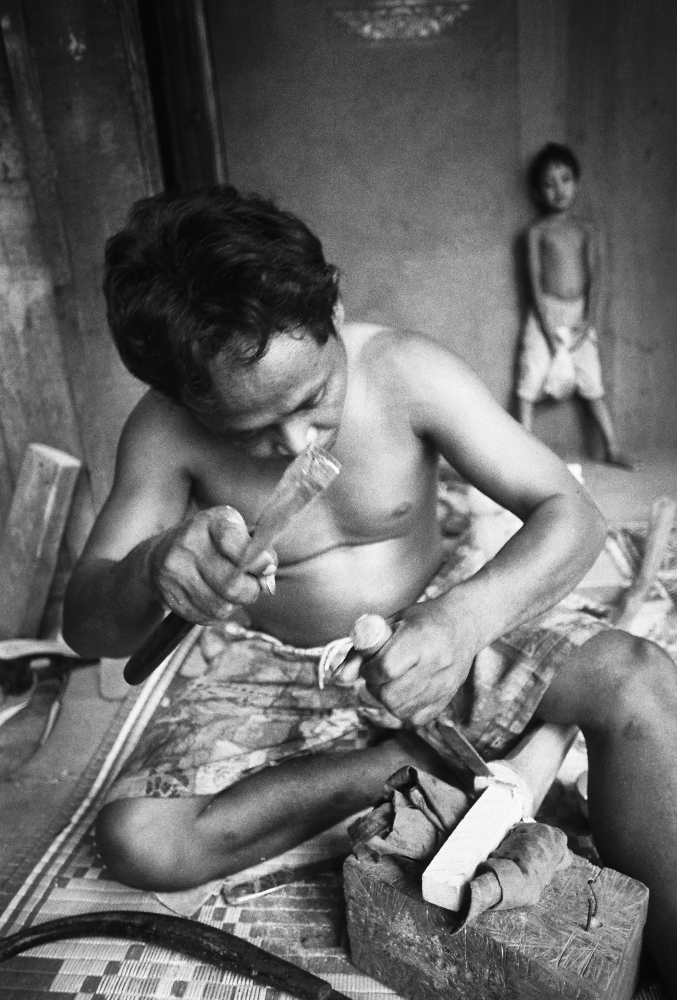

Lokru Meas Mary, Instrument Maker and Musician

Born 1960 in Angsnuol, Kandal

I started to make musical instruments for Pin Peat music when I was 18. I was not interested to learn at that time, but my father said that it’s a skill that he could pass to me. My father learned to make musical instruments from my grandfather. He told me that his great grandfather and his four friends made fake coins during the French protectorate era. The French administrators were curious why my great-great grandfather was so rich. When they discovered what he was doing, the French authorities chased him and his friends away. They all ran to the border and there they started to make Khmer musical instruments to earn a living. That’s the history I learned from my father.

So I learned to make instruments because I did not want to disappoint him. Unlike my father though, I learned also how to play the instruments we were making. Later on, I was invited to perform and that’s how I met my wife, Nou Narin. She was a Mohori and Ayai singer. At that time, we would sing and play music for ceremonies in exchange for rice. Back then, it was very hard for us to communicate because we did not have phones. So I would ride a bike from Psar Dey Huy to Psar Derm Thkov to find out if we were invited to perform somewhere. If we could get a lot of invitations we would go to sing and play music in a village for three or four days.

In 1992 we bought land and built a house in Dey Krahom, where it was cheap and it was an area of artists. Since my house was big, Master Tep Mary taught many students to play music there. In 2009, we were asked to leave. A day before they demolished my house, I went to join a birthday party in Siem Reap province. At around 2am, my nephew called and told us that they would destroy the whole area the next day.

I could not go in the middle of the night. But we took a plane the next morning and rode a motorbike to rush to our house. On arrival, we were extremely shocked to see our house being destroyed. My mother was crying and begging them to not destroy our house. She was old and was only able to take some clothes. There were a lot of instruments in that house, including instruments from the department of music, and it was all destroyed.

Those instruments were everything I had from my hard work over many years. At the end, nothing was left for me.

Lokru Meas Mary at his home on 25 September 2021

Master Tep Mary, Pin Peat Musician and Music Teacher

1933 – 2021, born in Kandal

“I personally think Chapei is like a diamond so I should not put a curtain to hide this treasure.”

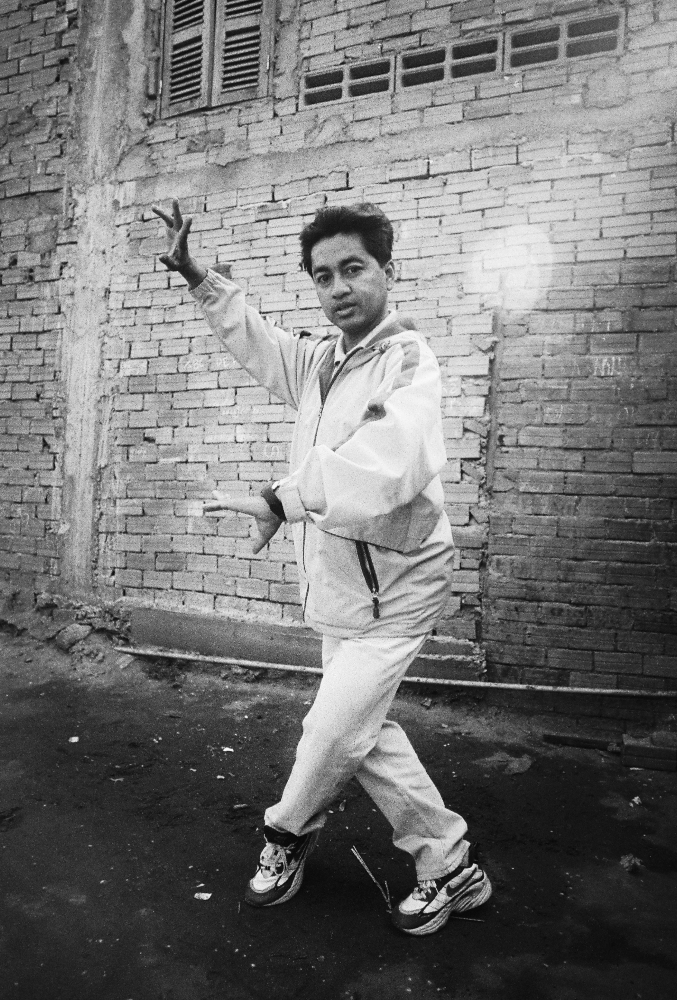

LOKRU PICH SARATH

Lokru Pich Sarath, Chapei Dong Veng Musician

Born 1980 in Daung Kpous Village, Takeo

I personally think Chapei is like a diamond so I should not put a curtain to hide this treasure. I learned to study Chapei in 2003. When I first came to Phnom Penh I was a trash collector. Since my family was very poor, I could not afford to rent a place to stay. So, I went to live in Neakvoan Pagoda. At that time, I went to study Ayai singing and Chapei Dong Veng at the Secondary School of Fine Arts. Ouch Savy was also a student there. She saw me living desperately and recommended me to study Chapei with Cambodian Living Arts. With CLA, I was able to study with Master Kong Nai from 2003 to 2007 in a class with Ouch Savy, Sin Sophea and Kong Boran, his son.

While I was studying at school and with Master Kong Nai, I also worked full time for an organization for health (HIV) advocacy. I would go to the parks and educate people about HIV. At first I was just a volunteer, but later on they gave me a paid job as a receptionist. I earned 60 dollars every month. I always get emotional when I look back at those times. My life was so difficult that I can’t find the words to describe what I have been through.

In 2007, I applied to be an arts teacher through the Ministry of Education and after two years training I was officially certified. Then in 2012 I accepted a job at CLA to replace Master Kong Nai after he retired. I have always thought that artists should have a job to be stable financially. I tell my students to find a job first, not to focus only on the arts. I don’t want them to end up like our masters. Sometimes they call me for support – they get nothing at the end of their lives.

In 2013, I founded the Community of Living Chapei. I learned that many masters were living in different areas and didn’t have a community to support them. I thought that I needed to create one because other artists had their own community.

I am committed to carry on their legacy and to help those masters.

Lokru Meas KimHeng, Dancer, Department of Fine Arts

“Thirty families were on the list to get an apartment as compensation, however, none of us moved there. The apartments still belong to us until now, but no one has moved to live there.”

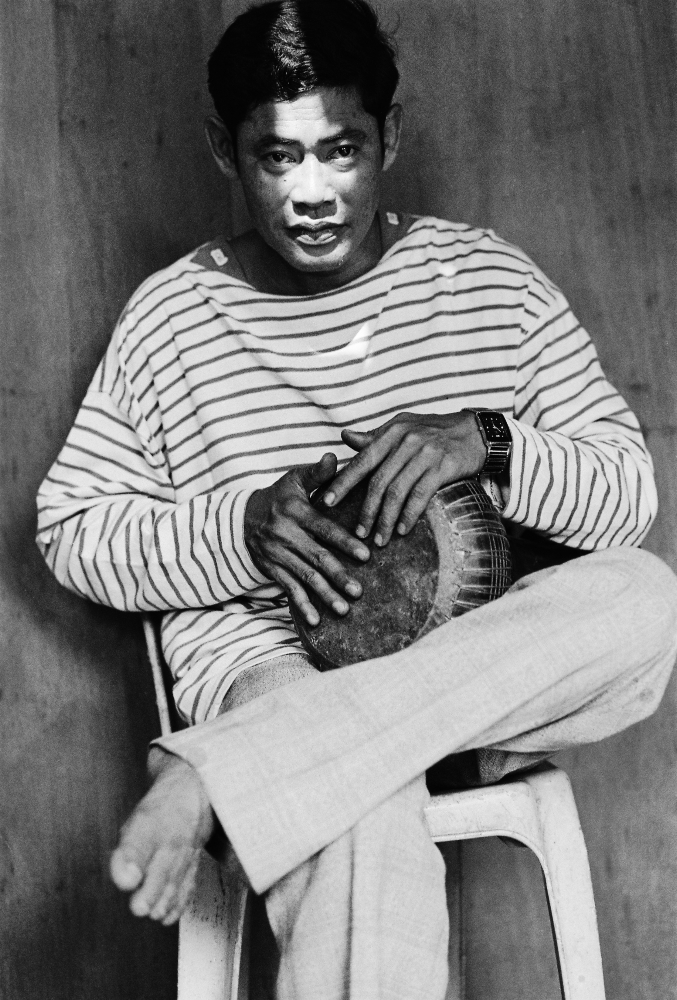

LOKRU MAO VUTHY

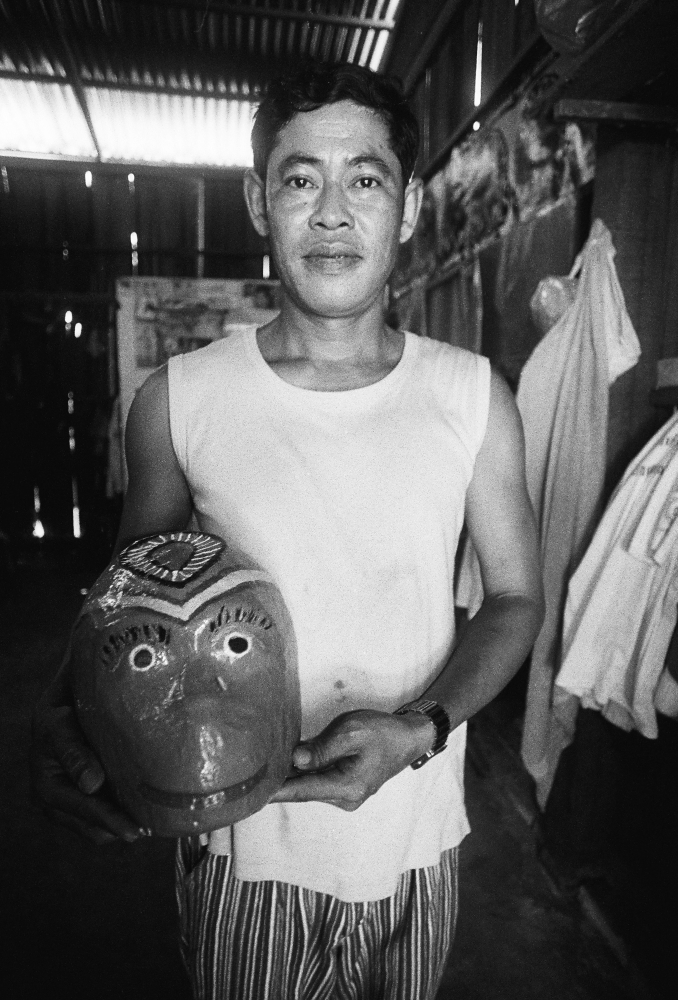

Lokru Mao Vuthy, Classical Dancer

Born 1960 in Phnom Penh

My father worked as a soldier at the Royal Palace. When I was six years old, he sent me and my younger sister to the palace to study performing arts. I learned Lakhorn Khoal [masked dance] and she learned Robam Boran [classical dance]. We performed in the palace for ceremonies a few times before the Khmer Rouge period. Since I was young, I performed the role of the little monkey for Lakhorn Khoal.

After the fall of Khmer Rouge in 1979, I was called to work in the old performing arts theatre. During that time I learned many other forms like: Lakhorn Yike, Lakhorn Bassac, Sbek Thom and Sbek Toch [shadow puppet] and traditional dance. I was sent to perform in many different provinces around Cambodia. Normally, I’d perform Yike Tum Teav and Mak Theung.

In 1994, I bought a house in Dey Krahom and lived there until they demolished all the houses in 2009. After the demolition, the private company and our government provided apartments in Damnak Troyeung to each family. Thirty families were on the list to get an apartment as compensation, however, none of us moved there. The apartments still belong to us until now, but no one has moved to live there.

Instead, I moved in with my children near Psar Depo. Since I am an artist, I also wanted my three children to be artists too. I sent them to art school when they were young. I sent my daughter to study classical dance in Siem Reap with her aunt. She was very committed and was a good dancer. However, when she got married, she stopped dancing because she said it can’t support her to survive. It was the same with my sons.

I traveled a lot for performance, joining troupes both small and large. I have performed in many countries including Australia, India, France, Italy and all the ASEAN countries. I mostly performed Robam Bropeynei. I retired from the Department of Performing Arts in 2018, however, I still work as a consultant for the ministry.